Judge Hails RI DD Progress But Calls For Critical Fixes

/By Gina Macris

For the first time since Rhode Island agreed a decade ago to correct civil rights violations affecting adults with developmental disabilities, people now routinely tell Court Monitor A. Anthony Antosh that their lives are better now than they were last year.

That’s a sign of success, said Chief Judge John J. McConnell, Jr. of the U.S. District Court in Rhode Island during a virtual hearing June 13 on the progress of a 2014 consent decree to reform past practices, such as restricting the work of people with disabilities to sheltered workshops.

Judge McConnell File Photo

Judge McConnell praised the “tremendous work” by the General Assembly and the state’s executive branch to dramatically increase funding for developmental disabilities, along with the roll-out of a community-facing system of services that went into effect July 1 of 2023.

At the same time, Judge McConnell said there are still some critical elements of the new system that must come into place for the state to fully implement the consent decree by the 2026 deadline, framing his compliments as “incentive to move forward, not to relax.”

Indeed, Judge McConnell plans to pick up the pace of his involvement in the short term. He gave lawyers for the state and the DOJ until July 12 to file plans for clearing the bottlenecks in the new system. Another court hearing is anticipated in August.

Antosh - file photo

Antosh, the monitor whom Judge McConnell appointed to track the progress of the reform effort, said in a recent report that he questions whether the state will be able to roll out high quality facilitation in time to meet the deadline for full implementation of the consent decree.

In looking at the positive steps the state has made, Judge McConnell contrasted the current status of the state’s efforts with the difficult period that followed signing of the consent agreement between the state and federal governments in 2014.

There were “years where the focus was lost and the state’s commitment was not obvious” for making constitutionally required changes to the service system, Judge McConnell said.

Among the progressive changes are increased community activity. About 84 percent of adults with developmental disabilities spend an average of nearly 16 hours a week participating in community activities, according to the most recent survey conducted by the Sherlock Center for Disabilities at Rhode Island College.

Transition Services Have Achieved Goals

For young people graduating from high school, coordination has improved between the local school districts, the state Department of Education and adult services, Antosh said.

The number of work experiences for high school students has increased and four of 14 who graduated in the last year went into paid employment, he said in a report. Antosh said the services that help young people make the transition to adulthood meet the criteria of the consent decree.

Although a workforce shortage among caregivers continues as part of a national phenomenon, the hike in wages for caregivers implemented last July means that Rhode Island has the lowest turnover rate in the nation in the field of direct care - at least in developmental disabilities, Antosh said. (Private-sector direct care workers in developmental disabilities make more than $22 an hour, on average. Beginning July 1, significant pay hikes will extend to other types of workers in community-based human services. Related state budget article here.)

Key Problems Remain

The remaining roadblocks to a fully realized program for people with developmental disabilities include:

• a lack of independent facilitators working with individuals to navigate the system

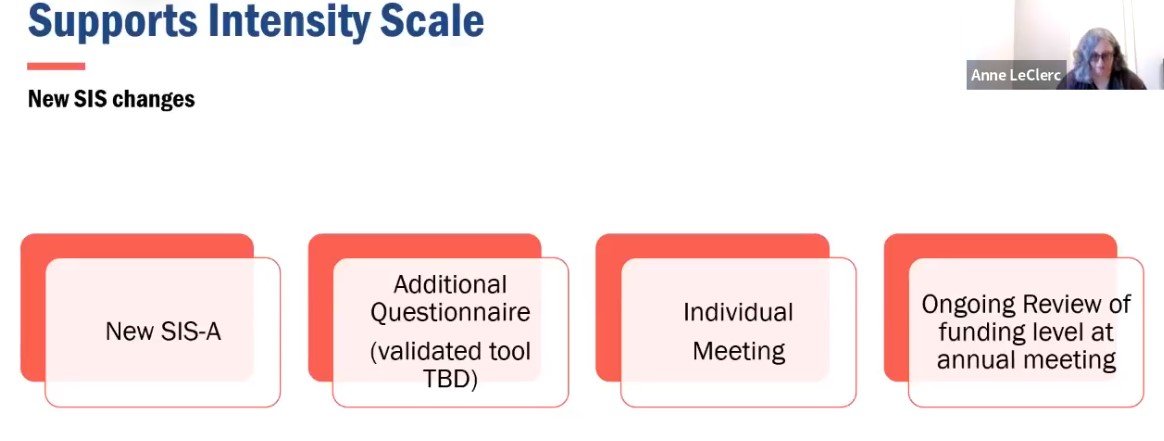

• an assessment process that does not yet capture all of a person’s needs

• new bureaucratic hurdles that prevent individuals from getting money from a new category of “flexible funding,” or “add-on” services.

The monitor’s biggest concern is that the state does not have independent facilitators in place to guide individuals through a new three-step assessment process and help them secure the necessary funding for a purposeful program of services.

These trained facilitators are critical in bringing all the pieces of a service system together in an individualized way to improve the lives of people with developmental disabilities, the monitor has said.

The state has budgeted nearly $2 million to hire 18 social workers to serve as facilitators in the next fiscal year, but the Director of the Division of Developmental Disabilities (DDD), Kevin Savage, said only two of them have begun working, as supervisors.

He said he shares “some of the monitor’s trepidation” about the facilitators. “The question is, are they going to be the right people,” Savage said. The facilitators will be funded through the Executive Office of Health and Human Services, not DDD.

The new three-step assessment process is not widely in place, Antosh said, and even when it is used, individuals do not understand how the more comprehensive sequence of questions and interviews is related to individual funding.

To fully comply with the consent decree, the state must get McConnell’s approval on the mathematical formula, or algorithm, that is used to translate needs for support services into individual budgets, according to one of Antosh’s recent reports.

The budgets must not serve to limit spending but to meet an individual’s needs and preferences, Antosh has emphasized.

When the new rate system and administrative structure was introduced last year, state officials said the more accurate assessment process would lead to a reduction in appeals of funding decisions. But the appeals continue.

The amount of money awarded on appeal is expected to be about $22 million in the current fiscal year, according to the May Caseload Estimating Conference. That projection is about $2,246,000 less than the last fiscal year. Last year’s $24.2 million was the highest awarded on appeal since 2015, when the amount reached $28 million, according to an email earlier this year from a spokesman for the state Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals (BHDDH).

As it is, participants have a difficult time accessing so-called “flex funding”, or add-on services, particularly employment-related supports, according to Antosh and Asst. U.S. Attorney Amy Romero, who represented the Justice Department. Romero said she knows former sheltered workshop employees who still haven’t seen the benefits of the consent decree in their lives, years after the workshops themselves have been shut down.

In May, the state reported that 348 persons had obtained add-on employment support, Antosh said, far below his expectations. The overall developmental disabilities caseload is about 4,300 people.

Individuals and families who direct their own services and have no links to provider agencies are at a heightened disadvantage in trying to get employment-related supports, Antosh and Romero said. About a quarter of the developmental disabilities caseload, or about 1,000 people, are in the “self-directed” category.

Antosh said individuals must not be forced to choose between between community activities and employment-related supports.

The monitor’s reports to the court give additional detail on clashes between the court’s intentions and the state’s interpretation of portions of the new service system.

The court intended that job coaching and job retention should be decided according to the needs of the individual, but those receiving services and their caregivers are being told there are time limits to these services, he said.

In March, Antosh wrote to the court that “the amount of hours of job coaching or job retention needed is unique to each individual.”

“This is an individual program decision, not a budgetary decision.” Antosh wrote in bold type in a report submitted in March.

The under-utilization of services is reflected in current spending, which is running about 17 percent under the original projections, said Brian Daniels, Director of the state Office of Management and Budget during the hearing before McConnell.

In reports to the court in recent months, Antosh said providers must file a new purchase order every time an add-on service occurs.

That means every time a participant goes to the gym with a caregiver, or goes to work with a job coach, a new purchase order must be filed for the transportation and the service of the caregiver.

And providers say that group home residents who stay home for whatever reason, including an inability to access add-on services, are funded at a lower annual residential rate now than they received a year ago. Even though their needs have not changed, they may have fewer staff at home. Residential services are not addressed by the consent decree.

Antosh, meanwhile, says he wants the state to simplify the bureaucracy around billing and reimbursements, echoing the complaint he had about the “administrative barriers” of the old system.

In addition, Antosh has said providers must be allowed to bill retroactively to July 1 of last year for “professional services,” which includes nursing, counseling, and some other services, because the state’s new billing system is not yet set up to accept those invoices.

Romero said the Justice Department is “cautiously optimistic” that the state will be able to comply with the consent decree in two years, but the DOJ remains concerned that money budgeted tor enhanced services, particularly employment-related supports, remains unused.

To read the monitor’s report dated June 10, 2024, click here

To read the monitor’s report dated March 25, 2024, click here