"Significant" Raises Proposed For RI DD Workers After Court-Ordered Talks

/By Gina Macris

RI Governor Dan McKee’s proposal to raise wages from $13.18 to $15.75 an hour for caregivers of adults with developmental disabilities might prevent a widespread worker shortage from getting worse.

But those who have had the frustrating experience trying to recruit and retain workers at the current lower rate told the House Finance Committee June 10 that the proposed raise, while significant, will not be enough to ease the labor crisis that prevents the state from complying with a 2014 civil rights consent decree affecting adults with developmental disabilities.

Other advocates made the broader statement that that paying a living wage to caregivers of all vulnerable populations is a moral imperative. Raising pay to attract more workers also is essential to guaranteeing the civil rights of vulnerable people, no matter what their disability, they said.

The Integration Mandate of the Americans With Disabilities Act, (ADA), reinforced by the 1999 Olmstead decision of the U.S. Supreme Court, says that those with disabilities have a right to receive the services they need to live regular lives in their communities.

If the state does not adopt a comprehensive Olmstead plan to provide integrated, community-based services to all people with disabilities, it will remain vulnerable to more litigation like the ADA complaint of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) which led to the 2014 consent decree, said a spokesman for the Rhode Island Developmental Disabilities Council.

As it is, Rhode Island’s Director of the Division of Developmental Disabilities acknowledged at the House Finance Committee hearing that the state has a “difficult relationship” with the U.S. District Court and the DOJ over the status of implementation and the unfinished work ahead as the agreement nears its conclusion in 2024.

I/DD Population Sitting At Home

Seven years after Rhode Island signed the consent decree, agreeing to end the segregation of sheltered workshops and day care centers, many adults with developmental disabilities are no better off.

For example, Jacob Cohen of North Kingstown, who once had a full schedule of activities in the community, now gets only three hours a week of support time, his father, Howard, told the Finance Committee in written testimony.

At AccessPoint RI, a Cranston-based service agency, 50 of 109 supervisory and direct care jobs are vacant and 60 out of 160 clients are not getting any daytime services, according to the executive director.

The consent decree calls for 40 hours a week of employment-related supports and other activities in the community.

A consultants’ report commissioned by providers says the private service providers lack 1,081 of the 2845 full time direct care workers they need to carry out the requirements of the consent decree. COVID-19 exacerbated the workforce shortage but did not cause it, the consultants said. The consultants said that depending on living arrangements, persons with developmental disabilities have experienced a reduction in services ranging from 49 percent to 71.6 percent, with those in family homes having the severest cutbacks.

The McKee administration’s proposed $15.75 hourly reimbursement rate would represent a wage hike of about $2.50 or more for direct care workers – roughly 20 percent.

The state does not set private-sector wages directly but reimburses the private agencies for wages and employment-related overhead, like taxes and workers compensation. Some providers pay a little more than the current hourly minimum of $13.18, by subsidizing wages with revenue from other types of services.

In addition to raising direct care worker pay, the proposal would raise reimbursement levels for supervisors’ wages from $18.41 to $21.99. There would be no raises for support coordinators or job developers, who are paid $21.47 an hour. Nor would those in a catch-all “professional” category receive a pay increase. They are paid $27.52 an hour, according to a presentation the House Fiscal Advisor made to the Finance Committee.

The overall wage increase would cost a total of $39.7 million in federal-state Medicaid funding, including $16.8 million in state revenue and $22.9 million in federal reimbursements.

Of the state’s share of the cost, $13 million would be re-directed from a $15 million “transition and transformation fund” for developing systemic reforms aimed at quality improvement and the reimbursement model that pays private providers. The reimbursement model was redesigned a decade ago to favor segregated care and has not been fundamentally changed since then.

Robert Marshall, the spokesman for the Rhode Island Developmental Disabilities Council, warned that gutting the so-called “transition and transformation fund” could heighten the state’s non-compliance with the consent decree and leave it open to additional federal action.

House Fiscal Office

With the governor’s proposed raises included, the allocation to the private developmental disabilities system would jump from $260.3 million in federal-state Medicaid funding in the current fiscal year to $297.7 million, an overall increase of $37.4 million, according to the presentation of the House Fiscal Officer, Sharon Reynolds Ferland.

Tina Spears, executive director of the Community Provider Network of Rhode Island (CPNRI), a trade association which negotiated the wage hike with the state, called it a “notable first step in rebuilding the workforce serving people with intellectual and developmental disabilities.”

SPEARS CPNRI

“This wage increase will improve the lives of both those who do the work and the families who are served by that work,” she said in written testimony.

But Spears, who had pressed for a rate of $17.50 an hour, told the committee that the state’s final offer of $15.75 does not make it competitive in attracting new workers.

Complicating the salary issue, the administration expects the private agencies to accept group home residents from the state-run developmental disabilities system, which it plans to phase out. The current allocation of $29.7 million for state-run group homes, named Rhode Island Community Living and Supports (RICLAS) would be cut to $9 million in the next budget.

Both the unions representing RICLAS workers and the private providers have expressed skepticism that the privatization is feasible.

The budget calls for the reduction of 50 RICLAS positions. RICLAS pays workers a starting rate of about $18.55 an hour, more than $5 above the current entry-level pay in the private system, and about $2.80 above the proposed new private-pay rate.

On July 1, minimum wages in Connecticut will increase to $16.50 an hour for private-sector direct care workers in the first year of a two-year contract between that state and the Service Employees International Union (SEIU). The rate will jump to $17.25 on July 1, 2022.

Massachusetts will pay direct care workers at privately-run agencies a minimum of $16.10 an hour beginning July 1, the final year of a three-year contract with another branch of the SEIU, according to a salary schedule on a Massachusetts state website related to “personal care attendants.”

Massachusetts already siphons off some of Rhode Island’s best caregivers, said Michael Andrade, President of CPNRI and CEO of Pro-Ability at the Bristol County ARC.

Ruggiero Capitol TV

During the hearing, Rep. Deborah Ruggiero asked Jonathan Womer, Director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), to tell her who has been leading the state’s response to the consent decree during the last few years and explain why there has been “so little progress.”

She also wanted to know why she’s hearing reports that the state is “not in very good standing” with the Court or the DOJ and what is being done to change that situation.

Womer introduced Kevin Savage, who has been in charge of the Division of Developmental Disabilities since last July.

“While we haven’t met a number of benchmarks for getting people to work” in the community, Savage said, “there are no longer any sheltered workshops in Rhode Island.”

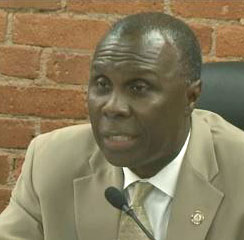

SAVAGE

“That’s a major achievement of the consent decree,” Savage said. He added that because of the pandemic, meeting goals for employment and community integration has been “extremely challenging,”

During state budget preparations, which began last fall during great economic uncertainty, OMB asked state agencies to submit proposals with 15 percent reductions in their spending plans. The economic outlook has brightened considerably since then.

In January, Chief Judge John J. McConnell, Jr. of the U.S. District Court said Rhode Island must raise direct care wages to $20 an hour by 2024 to attract more direct care workers to Rhode Island providers, who do the work in the field necessary to enable the state to comply with the consent decree.

Two months later, in March, the governor submitted a budget proposal that offered no raises. Then came court-ordered negotiations, which resulted in the administration’s proposal for the $15.75 rate, as well as a separate budget amendment that would comply with another court order, making the developmental disabilities caseload part of formal, consensus-building state budget preparations in November of this year.

During the budget hearing, Savage said, “We are having a difficult time in our relationship with the Court. We do want to repair that.”

“We have tremendous respect for the judge and tremendous respect for the court monitor. We work with some of the best providers you can work with, so it’s really not a matter of not wanting to work with the providers or the court monitor,” Savage said.

The negotiations took too long, he acknowledged.

“We need to pick up the pieces and move forward faster,” he said, engaging the community “much more robustly than we have.”

“We need to get to get to $20 by 2024,” to “stabilize the workforce,” and make other reforms as part of a court ordered, comprehensive three-year compliance plan, he said.

Rep. Alex Marszalkowski, D- Cumberland, chairman of the Human Services Subcommittee of the House Finance Committee, asked why the wage increases would apply to group home workers when the consent decree is limited to issues related to daytime services.

Savage responded that “if we stabilize one part of the workforce, we destabilize the other; the only path is to stabilize the entire system.”

Emphasis on Civil Rights

Later in the hearing, Spears, the CPNRI director, emphasized that hard-working caregivers deserve a living wage and noted that “civil rights protections” are at the heart of the 2014 consent decree. “It’s essentially a corrective action plan to resolve civil rights violations and make sure they never happen again,” she said.

She added: “We are seven years into a ten-year agreement, and there is a tremendous amount of pressure from the Court and the U.S. Department of Justice to achieve the established benchmarks.” As it now stands, the private sector cannot deliver on the compliance the state needs, Spears said.

The Chair of the Long Term Care Coordinating Council (LTCCC) and the representative of the Developmental Disabilities Council each applied a broader perspective on the budget amendments, saying the General Assembly must address the workforce and quality-of-life issues across all vulnerable populations.

Maureen Maigret, chair of the LTCCC, recommended the General Assembly use some of the current Medicaid reimbursement rate, enhanced under provisions of the American Rescue Plan Act, to raise the wages of direct care workers funded by Medicaid’s Home and Community Based Services (HCBS) to the same level proposed for those working in developmental disabilities.

“The issues facing other types of home and community-based services and residential programs are similar to providers of services for persons with developmental disabilities,” Maigret said in written testimony, citing low wages, high turnover and staff burnout, all exacerbated by the pandemic.

“And we know that almost a majority of these workers are women and persons of color whose value has historically been under-valued,” Maigret said.

“Efforts to achieve wage parity for all direct care staff working in government-subsidized Home and Community-Based Services (HCBS) is imperative if the state is to have a quality and accessible LTSS (Long Term Services and Supports) system with appropriate options for persons needing care,” she said.

Marshall, of the DD Council, said Rhode Island could use some of the one-time stimulus funding under provisions of the American Rescue Plan Act to develop an Olmstead plan, a multi-year blueprint for conforming to requirements of the ADA’s Integration Mandate.

Only seven states — Rhode Island among them - still lack such a plan, he said.

Because of the Olmstead decision, Medicaid changed the rules of Home and Community-Based Services programs to help vulnerable persons live as independently as possible at home or in home-like settings.

Marshall said Rhode Island has been in violation of Medicaid’s regulations on home and community-based services since 2014 and is “vulnerable to yet another Department of Justice lawsuit or ineligibility for federal Medicaid match.”