Former Training Through Placement building at 20 Marblehead Ave., North Providence RI

By Gina Macris

A federal judge has taken the state of Rhode Island to task for failing to keep track of a former sheltered workshop that has continued to segregate adults with developmental disabilities, despite a landmark integration agreement four years ago that seeks to transform daytime services for those with intellectual challenges.

An order by Judge John J. McConnell, Jr. of U.S. District Court sets strict deadlines between the end of June and the end of July for specific steps the state must take to ensure that all clients of the former sheltered workshop lacking jobs or meaningful activities begin to realize the promise of the 2013 agreement.

The so-called Interim Settlement Agreement of 2013 focused primarily on special education students at the Birch Academy at Mount Pleasant High School and adult workers at Training Through Placement (TTP), which has become Community Work Services (CWS.)

The former sheltered workshop used Birch as a feeder program for employees, who often were stuck for decades performing repetitive tasks at sub-minimum wages – even when they asked for other kinds of jobs. Involved are a total of 126 individuals, according to McConnell’s count.

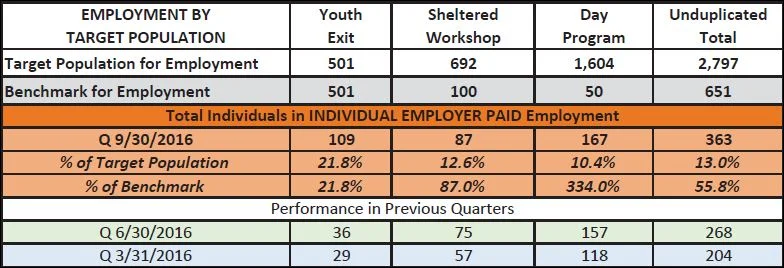

In 2014, after a broader investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice, the state signed a more extensive consent decree covering more than 3,000 adults and teenagers with developmental disabilities. The state promised to end an over-reliance on sheltered workshops throughout Rhode Island and instead agreed to transform its system over ten years to offer individualized supports intended to integrate adults facing intellectual challenges in their communities.

Together, the companion agreements made national headlines as the first in the nation that called for integration of daytime supports for individuals with disabilities, in accordance with the Olmstead decision of the U.S. Supreme Court. The Olmstead decision re-affirmed Title II of the Americans With Disabilities Act, which says services must be provided in the least restrictive setting which is therapeutically appropriate, and that setting is presumed to be the community.

McConnell’s order is the latest and most forceful development in a story that highlights not only the failings of the former sheltered workshop, Training Through Placement (TTP), but the state’s lack of a comprehensive quality assurance program for developmental disability services system-wide.

The former sheltered workshop run by CWS at 20 Marblehead Ave., North Providence, was closed by the state on March 16 on an emergency basis because of an inspection that showed deteriorating physical conditions. Individuals with developmental disabilities were “exposed to wires, walkways obstructed by buckets collecting leaking water, and lighting outages due to water damage,” according to a report to the judge. At that point, CWS had been working under state BHDDH oversight for about a year, because of programmatic deficiencies, according to documents filed with the federal court.

CWS is a program of Fedcap Rehabilitation Services of New York, which had been hired by then-BHDDH director Craig Stenning to lead the way on integrated services for adults with developmental disabilities at TTP in the wake of the 2013 Interim Settlement Agreement. Stenning now works for Fedcap.

With the CWS facility closed by the state, the program resumed operations on March 21 in space provided by the John E. Fogarty Center in North Providence under terms of a probationary, or conditional, license with state oversight, according to a report of an independent federal court monitor overseeing implementation of the 2013 and 2014 civil rights agreements in Rhode Island that affect adults with developmental disabilities.

The monitor said the state licensing administrator for private developmental disability agencies also notified the CWS Board of Directors and the Fedcap CEO of the situation, making these points:

- the state was concerned about unhealthy conditions of the CWS facility

- ·the agency failed to notify the state of the problems with the building

- CWS failed to implement a disaster plan

- ·The CWS executive director had an “inadequate response” to the state’s findings.

The letter to the Fedcap CEO also said that CWS had been providing “segregated, center-based day services” rather than the community-based programming for which the agency had been licensed.

Summarizing the status of the 2013 Interim Settlement Agreement, the monitor, Charles Moseley, concluded in part that the Providence School Department and the Rhode Island Department of Education have continued to improve compliance through added funding, an emphasis on supported employment, staff training and data gathering and reporting.

Overall, the state Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals, (BHDDH) the Executive Office of Health and Human Services, (EOHHS) and the state Office of Rehabilitation Services (ORS) also have made progress, Moseley said, citing budget increases, new management positions, and programmatic changes he has mentioned in various status reports on the statewide consent decree.

However, progress for clients of the former TTP workshop “appears to have plateaued and possibly regressed,” Moseley wrote, and for that he faulted the successor agency, CWS, and the lack of sustained oversight on the part of BHDDH.

While some former sheltered workshop employees at TTP did find work after the Interim Settlement Agreement was signed in 2013, “the number and percentage of integrated supported employment placements has remained essentially flat for the last four years,” he said.

Efforts to reach CWS and Fedcap officials were unsuccessful.

In mid-March, CWS reported that 30 of 71 clients on its roster had jobs. Of the 30 who were employed, 13 with part-time jobs also attended non-work activities sponsored by the agency. In addition, 41 clients attended only the non-work activities.

In early April, Moseley and lawyers from the DOJ interviewed the leadership and staff of CWS and some of the agency’s clients in their temporary base of operations at the Fogarty Center. Serena Powell, the CWS executive director, was among those who attended, Moseley said.

The leadership “revealed a lack of understanding of the basic goals and provisions of the state’s Employment First policy and related practices,” Moseley said in his report.

Rhode Island has adopted a policy of the U.S. Department of Labor which presumes that everyone, even those with significant disabilities, is capable of working along non-disabled peers and enjoying life in the community, as long as each person has the proper supports.

“This lack of knowledge and understanding appeared to extend to the basic concepts of person-centered planning (individualization) and program operation,” Moseley said, citing the names of specific protocols used by state developmental disability systems and provider agencies “across the country.”

Moseley said some CWS staff do not have the required training to do their jobs.

Some job exploration activities have consisted of “little more than walking through various business establishments at a local mall,” Moseley said, explaining that they were not purposeful activities tailored to individual interests and needs.

Moseley said he interviewed three clients of CWS and they were “unanimous in their desire to have a ‘real job’ in the community and to be engaged in productive community activities that didn’t involve hanging out with staff at the mall.

“All three persons reported that they were pleased to be out of the CWS/TTP facility and to have opportunities to go into the community more often. Two of the three expressed an interest in receiving services from a different service provider,” Moseley said.

The state has had four years to work on compliance with the Interim Settlement Agreement and the Consent Decree. During that time, BHDDH has seen three directors and its Division of Developmental Disabilites (DDD) has had four directors, including an outside consultant who served on an interim basis part of the time officials conducted a search that led to the appointment of Kerri Zanchi in January.

Between mid-February and early May, there was a separate upheaval in the leadership of the Executive Office of Health and Human Services, which had taken charge of the state’s compliance efforts in connection with the 2013 and 2014 civil rights agreements.

In a statement to the court, Zanchi alluded to all the turnover, saying that “progress has been challenged due to changes in internal and external leadership impacting stability, communication, resources, accountability, and vision.”

Zanchi suggested that budget increases and considerable effort among BHDDH and ORS staff during the last year to improve compliance nevertheless have not been enough to make up for the previous three years of inaction.

Among other things, there is no consensus across the network of private service providers – some three dozen in all – “regarding the definition and expectation of integration,” Zanchi said.

DDD is responding by establishing “clear standards, training and monitoring,” she said. McConnell’s order required DDD to complete “guidance and standards for integrated day service” by June 30 and allowed another month for the document to be reviewed and disseminated to providers.

Zanchi said the state now has an “extensive quality management oversight plan” with CWS that involves DDD social workers, who are actively supporting CWS clients and their families. These same social workers also have average caseloads of 205 clients per person, according to the most recent DDD statistics.

Zanchi agreed with Moseley, the court monitor, that “current review and monitoring does not constitute a fully functioning quality improvement program.”

Moseley said that DDD’s quality improvement efforts “are seriously hampered by the lack of sufficient staff.” He called for “additional staffing resources” to ensure quality, provide system oversight and improve and ensure that providers get the required training.

Zanchi said an outside expert in interagency quality improvement is working with the state to develop and implement such a fully functioning plan. McConnell gave the state until July 30 to have a “fully-developed interim and long-term quality improvement plan” ready to go.

Of the 126 teenagers and adults McConnell said are protected by the 2013 Interim Settlement Agreement, 46 need individualized follow-up. Of the 46, 34 have never been employed, including 24 former TTP workers and 10 current Birch students or graduates.

The judge reinforced the monitor’s repeated emphasis over the last two years on proper planning as the foundation for producing a schedule of short-term activities and long-term goals that are purposeful for each person, whether they pertain to jobs, non-work activities, or both.

These planning exercises, led by specially trained facilitators, can take on a festive air, with friends and family invited to share their reminiscences and thoughts for the future as they support the individual at the center of the event.

McConnell’s order said the state must ensure that “quality” planning for careers and non-work activities is in place by July 30 for active members of the protected class who want to continue receiving services.

Among CWS clients, the agency reported that 10 have indicated a reluctance to go into the community, perhaps because they feel challenged by the circumstances.

Moseley cited a variance to the Employment First policy developed by the state to cover those who can’t or don’t want to work, for medical or other reasons. Moseley’s report said he approved the variance in 2015, but it hasn’t been implemented. He acknowledged that it was difficult to understand.

McConnell’s highly technical and detailed order requires the state to implement a “variance and retirement policy” by June 30 “to discern specifically those who do not identify with either current or long-term employment goals.”

McConnell also ordered the state to fund an additional $50,000 worth of training from the Sherlock Center on Disabilities at Rhode Island College so that those who work with adults with developmental disabilities can give them individualized counseling about how work would affect their government benefits.

The monitor has repeatedly cited a dearth of individualized benefits counseling. In his latest report, he wrote that in interviews May 11 and May 12, high school students at Birch, their parents, staff, and others expressed the false conviction that students could work no more than 20 to 25 hours a week without compromising their benefits.

"This finding underscores the importance of individualized benefits planning for this population to ensure that students are able to take full advantage of Social Security Act work incentives that may enable them to work more than 25 hours per week while maintaining their public and employer benefits," Moseley said.

The monitor is expected to evaluate compliance with the deadlines in McConnell's latest order in a future status report.