RI Governor Seeks Tens of Millions More For DD To Expand Community Services

/By Gina Macris

This article has been updated

Rhode Island Governor Dan McKee has more than doubled the hike he is seeking from the General Assembly for developmental disabilities services in the next fiscal year. The overall funding increase is intended to expand opportunities for people to participate in community activities and increase the direct care workforce by offering higher pay.

A consultant for the state alluded to the funding hike during an April 27 hearing before Chief Judge John J. McConnell Jr. of the U.S. District Court, who heard a progress report on the state’s implementation of a 2014 consent decree intended to integrate adults with developmental disabilities in their communities. The amount of the increase was not mentioned in court but appears in updated documents on the website of the state budget office.

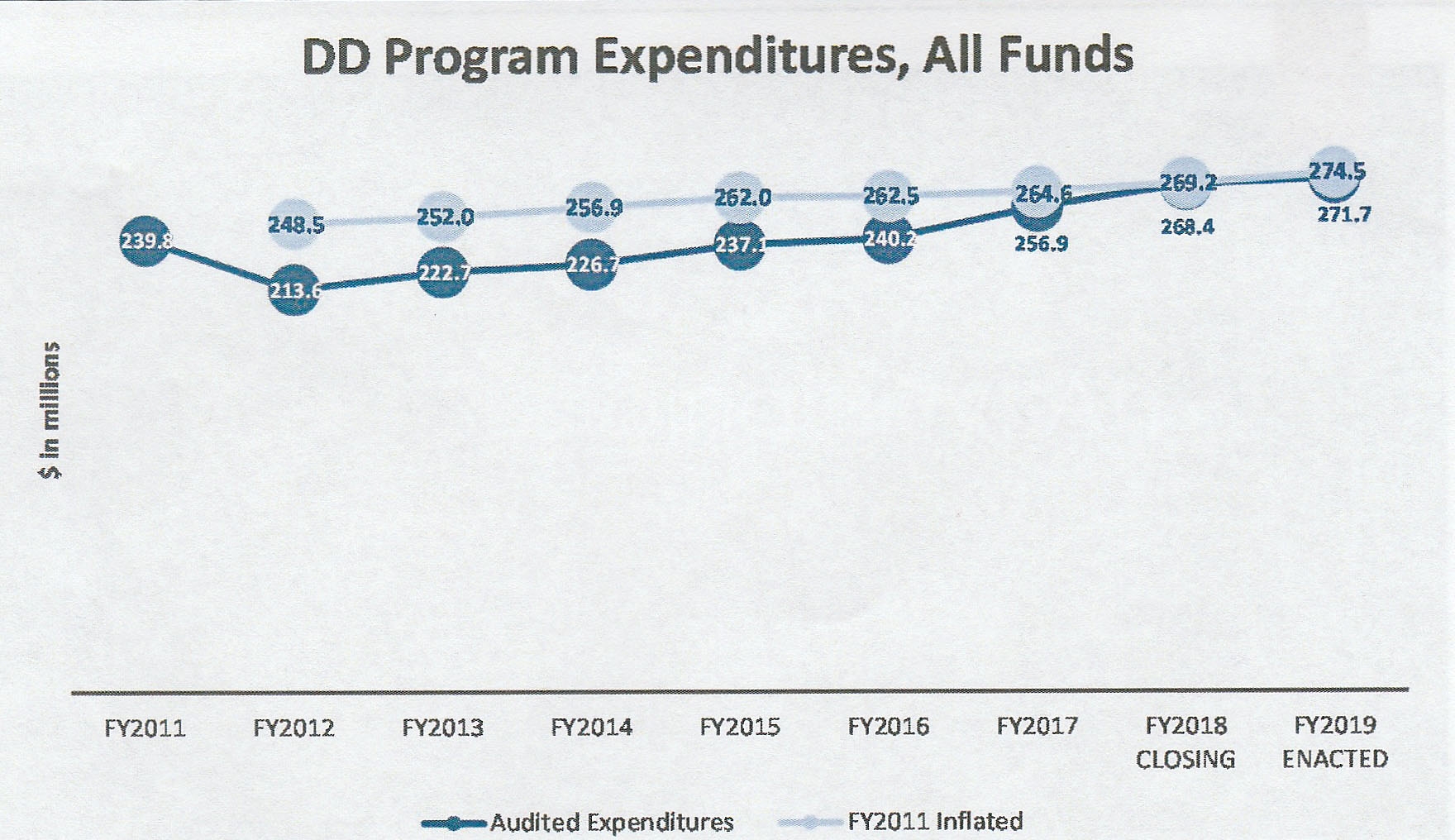

McKee originally earmarked $30.8 million to raise the minimum wage for direct care workers from $18 to $20 an hour to comply with a court order. The raises were to be part of a $385 million spending limit for private developmental disabilities services for the fiscal year beginning July 1.

On April 17, the state budget office raised the set-aside for raises to $75 million, including about $33.9 million in state revenue and about $25.8 million from federal funds in the federal-state Medicaid program. The budget amendmentes the new total for the private developmental disabilities system to $429.5 million.

The dramatic hike in funding anticipates a significant policy change that will allow private service providers to bill at higher rates on the assumption that all activities will involve supports in the community and will require more intensive staffing than center-based care.

Maintaining a regular gym schedule, attending an art or dance class, meeting a someone for coffee or going shopping are all activities most people take for granted, but those with developmental disabilities often need help with transportation and other supports to make these things happen.

The shift to 100 percent community-based services would eliminate the practice of budgeting for 40 percent of each client’s time in a day care center, which requires less intensive staffing but doesn’t offer people individualized or purposeful choices. A group cooking class, for example, may not succeed in teaching skills enabling participants to cook more independently at home.

The so-called “60-40” split between community and center-based care has been criticized by an independent court monitor overseeing the consent decree, who said the state must do everything it can to promote integration in the community to fully comply with the agreement.

The state’s consultant in a court-ordered rate review of Rhode Island’s developmental disabilities system explained the change in approach to daytime services during the April 27 hearing before Judge McConnell.

Stephen Pawlowski, managing director of the Burns and Associates Division of Health Management Associates, (HMA-Burns), said those who want center-based care may still choose it.

The recommendations of the HMA-Burns rate review, as well as the money to go with them, will need General Assembly approval before they go into effect July 1.

Feds Want Results

During the hearing, the independent monitor, A. Anthony Antosh, and a Justice Department lawyer, Amy Romero, applauded the administrative efforts of the state in recent months.

At the same time, they warned that full compliance with the consent decree will depend on results – more adults with developmental disabilities holding jobs and more community connections. And the deadline for full compliance is only 14 months away, June 30, 2024.

Romero, an Assistant U.S. Attorney in Rhode Island, previously raised concerns about the state meeting the 2024 deadline.

In the latest hearing, she commended the state for its efforts in the rate review process, but she also said the state must bring a sense of urgency to the push for more employment – one of the chief goals of the consent decree.

In frequent meetings with adults with developmental disabilities, she said, “meeting somebody with a job is the exception.”

“There are a lot of people out there who want to work and are not working,” she said. “It’s a missed opportunity with the employers themselves.”

The rate review would make employment-related supports available to everyone as an add-on to individual basic budgets.

Under the current rules, employment-related supports come at the expense of something else in the basic budgets. As a result, the number of overall service hours are reduced, because services like job development and job coaching cost more than other categories of support.

Since the consent decree was signed in 2014, the General Assembly has periodically earmarked separate funding for pilot employment programs in the developmental disabilities budget that don’t require individuals to give up service hours. The most recent one ended a year ago, shortly after the chief of employment services in the Division of Developmental Disabilities (DDD) departed.

A new employment chief will start work May 8, according to a spokesman for the Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals (BHDDH).

Some adults with developmental disabilities have been able get around the restrictions of the basic budgets if they have a service provider who gets funding for job supports from the Department of Labor and Training, or if they can get help from the Office of Rehabilitation Services.

And some high school students with developmental disabilities have gone from internships to real jobs as they move on to adult developmental disability services, although they have been the exceptions.

A spokesman for the Rhode Island Department of Education (RIDE) told the monitor, Antosh, that the agency is helping school districts plan revisions to transition services to put a greater emphasis on job-seeking.

Assessment Issues Remain

During the hearing, Antosh brought up another piece of unfinished business that poses a challenge for the state; figuring out how to apply the new rate structure so that everyone approved for services gets the supports they need.

The shift to community-based day services, by itself, will not achieve that goal, because of the way the assessment of individual needs is currently linked to funding.

Antosh said he continues to hear from families who are concerned about the accuracy of the assessment in its existing form.

The algorithm – or mathematical formula – used to turn the scores from the assessment into individual funding “needs to change,” he said. The assessment itself was not designed as a funding tool, but the developer, the American Association of Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD), still allows many states to use it that way.

After Rhode Island began its rate review in early 2022, AAIDD announced it would spend the next year overhauling the assessment, called the Supports Intensity Scale (SIS).

The second edition of the SIS was not released until mid-March of this year, and the state won’t begin to use the revised assessment until June. After that, a sample of 600 assessments will be needed before officials can do the math in a systematic way to assign budgets.

With each assessment taking two to three hours per person, the process of collecting 600 sets of scores is expected to take about six months.

In addition, the way the second edition of the SIS is scored is substantially different than the first edition, said Pawlowski of HMA-Burns.

Heather Mincey, Assistant Director of DDD, said that going forward, the SIS will not be the only measure used to determine support needs.

The second edition of the SIS will come with supplemental questions to capture exceptional needs like behavioral and medical issues.

But Mincey said there will be an additional set of supplemental questions, as well as an interview with individuals and their families to determine if there is any support need the assessment missed.

Independent facilitators will work with the assessment results to help individuals and families plan a program of supports, and then the funding will be assigned.

Currently, the funding is assigned directly from the SIS scores, and services are planned to fit the budgets.

Antosh has said the existing approach does not allow for the individualization necessary to comply with the consent decree.

The individual facilitators, proposed by Antosh, would be trained in a “person-centered” approach that incorporates short-term and long-term goals into a purposeful program of services built around the preferences and needs of the individual involved.

The person-cantered approach is considered a “best practice” in developmental disabilities that preserves people’s right to lead regular lives in their communities in compliance with the Olmstead decision of the U.S. Supreme Court, which gives the consent decree its legal authority. The Olmstead decision reinforced the Integration Mandate of the Americans With Disabilities Act.

The facilitators for person-centered planning have not yet been hired.

Mincey said the state is working with the Sherlock Center on Disabilities at Rhode Island College to develop a job description for the facilitators. They would not be state employees.

Governor’s Budget Amendments

In separate budget amendments on April 17, the Governor asked the General Assembly for additional funding to pay for the technology needed for them to do their jobs.

It calls for an information technology contract totaling $250,00 for so-called “conflict-free case management” to be implemented by the facilitators. All but $25,000 would be federal funds.

Antosh also asked Mincey what the state is doing to improve communication with families, who will have to absorb a considerable breadth of new information to take advantage of new opportunities in developmental disability services.

She highlighted the eight new positions being added to the staff of the Division of Developmental Disabilities who will focus on communication and training. All but one position has been filled, according to a BHDDH spokesman, Two have begun work, he added later.

Those new positions will cost $203,275 for the first full year, taking into account federal Medicaid reimbursements and savings from staff turnover in other positions, according to the governor’s original budget proposal.

The April 27 hearing serviced as an interim progress report as the state bears down on a court-ordered July 1 deadline to implement rate hikes and other administrative changes.

Antosh said he plans to write an evaluation of the state’s progress about mid-July. Judge McConnell said he will hold the next consent decree hearing about August 1. The exact date, later published by the court, is Tuesday, August 1 at 10 a.m, with public access available remotely.

The current developmental disabilities budget is $383.4 million, including nearly $352.9 million for the privately-run system and nearly $30.6 million for the state’-run group home network, which is not involved in the consent decree.

The governor’s revised budget for the current fiscal year would pare overall developmental disabilities spending to $377.3 million by June 30, including about $348.5 million for the private system and about $28.3 million for the state group homes, called Rhode Island Community Living and Supports (RICLAS.)

For Fiscal 2024, the total federal-state Medicaid funding would be $461.8 million for the private and state-run systems, according to the amended budget proposal. That total includes about $429.5 million for the private system and about $32.4 million for the state-run system.

Related content:

McKee’s original budget proposal is covered in an article here.

Pawlowski presented a PowerPoint on updated “rate and payments options” to the court that has been released by the state. Read it here.