By Gina Macris

This article has been updated.

In a single day in 2011, the Rhode Island General Assembly slashed about $26.5 million, or 12.7 percent, from payments to private agencies which care for adults with developmental disabilities, some of the state’s most vulnerable citizens.

The massive cutback sent the privately-run developmental disability service system into a tailspin from which it has not yet recovered, even though the dollar amount has been restored.

Documents obtained by Developmental Disability News through public records requests indicate that the budget cutback was based on an unsupported assumption that the private agencies could uniformly deliver the same level of service with far less money.

Moreover, the records show how Project Sustainability, a set of regulations designed to assess the needs of persons with developmental disabilities and assign them a dollar value for services, seemed to function instead as an attempt to control spending – albeit with questionable success.

Today the Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals (BHDDH) spends more than $21 million a year to “supplement” funding authorizations for individual clients made through Project Sustainability. The supplemental payments amount to about ten percent of all the reimbursements the state makes to the private agencies. Much of the supplemental funding occurs when families and providers appeal the funding determinations successfully, making the case that the original authorizations were inadequate to provide needed services.

A spokesman for House Speaker Nicholas Mattiello defends Project Sustainability, saying that it’s brought accountability to disabilities spending.

Larry Berman said that “Project Sustainability changed a system that did not have a consistent payment model, could not provide information about what services were being provided or in what setting, and if any services were actually provided. It created a new billing system that could account for that.”

“All providers are paid uniform rates for the same services,” he said. Previously, each agency negotiated with the state Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities and Hospitals (BHDDH.) a monthly stipend for a bundle of services for each client.

Since 2011, the General Assembly has added $47 million to services for adults with developmental disabilities, Berman said.

Berman rejected the notion that the General Assembly contributed to conditions which led to a 2014 consent decree with the U.S. Department of Justice and ten years of federal oversight of the state’s developmental disability system, which ends in 2024.

Findings of the U.S. Department of Justice

In findings that led to the consent decree between the state and federal government, however, the DOJ linked Project Sustainability with violations of the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA).

It said Project Sustainability restricted individuals’ access to regular jobs and non-work activities in the community – opportunities for choice that are guaranteed under Title II of the ADA. The U.S. Supreme Court re-affirmed Title II in its 1999 Olmstead decision, saying that individuals with all types of disabilities are entitled to receive services in the least restrictive environment that is therapeutically appropriate. And that environment is presumed to be the community.

In its findings, the DOJ noted that the “precipitous state budget cuts in 2011” exacerbated the problem of retaining qualified staff – a problem that today is described by providers as a “crisis”, despite an incremental pay raise to direct-care workers adopted in the current budget. Workers would get a second small raise in the next fiscal year, according to the budget proposal of Governor Gina Raimondo.

RI Allowed Less Money Than Provider Costs

To understand how the BHDDH budgeting process got more than $20 million off course, a history of Project Sustainability is in order.

In 2011, then-Governor Lincoln Chafee recommended $10 million to $12 million in cuts to developmental disability services, but the leadership of the General Assembly wanted bigger reductions. It first sought to limit eligibility, but backed off when an outside healthcare consultant under contract to BHDDH advised against it, according to a memo obtained through a public records request.

The consultant, Burns & Associates, said restricting eligibility would probably violate the federal “maintenance of effort” requirement for federal Medicaid funding and would not be approved by the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services. All developmental disability services are funded through the federal-state Medicaid program.

Five days after that opinion, dated May 26, 2011, BHDDH sent the General Assembly a memo describing a “methodology” for steep cuts to dozens of reimbursement rates, most of them between 17 and 19 percent below a target rate that was established after a year’s research that included data from the providers themselves on their costs. In undercutting that “target” rate, BHDDH said that the state could not afford to spend more, the memo said.

“We did not reduce our assumption for the level of staffing hours required to serve individuals,” the memo said.

“In other words, we are forcing the providers to stretch their dollars without compromising the level of services to individuals,” said the memo.

Craig Stenning, who was BHDDH director at the time, recently declined all comment for this article and ended a phone conversation with a reporter before any questions could be asked.

The General Assembly doubled Chafee’s recommended reductions in reimbursements on the basis of a last-minute floor amendment in the House, after the public had been cleared from the gallery of the chamber, early the morning of July 1, the final day of the General Assembly’s regular session that year. The budgeted reduction was $24.5 million, but the actual cut eventually totaled $26.5 million, according to the state’s figures on actual spending.

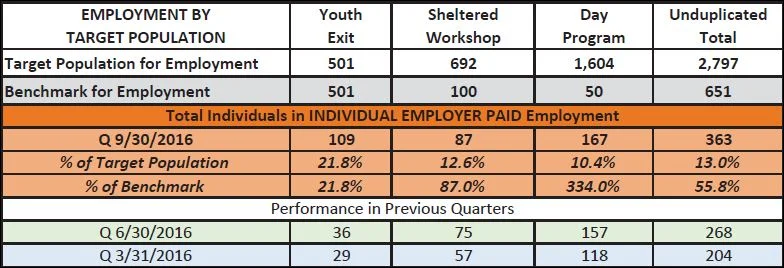

The vote also established Project Sustainability, the bureaucratic process - still largely in place today – that the DOJ later found violated the civil rights of clients of BHDDH. The primary elements:

- The Supports Intensity Scale (SIS), a standardized assessment designed to determine needed for an individual to accomplish his or her goalls.

- A formula or algorithm developed by Burns & Associates to assign funding to individuals according to one of five different levels or tiers, designated by letters A through E.

- A billing system that requires providers to document face-to-face time with clients in 15-minute increments in order for them to be reimbursed for day services.

Since 2010, BHDDH and the Executive Office of Human Services (EOHHS) have paid Burns & Associates about $1.4 million to introduce Project Sustainability, develop the equation, or algorithm, and monitor its use.

DOJ Cited "Seeming Conflict of Interest"

In challenging the state’s treatment of persons with disabilities in 2014, the Department of Justice found, at a minimum, “a seeming conflict of interest” in the way Rhode Island used the SIS as a “resource allocation tool”, because BHDDH both administered the assessment and determined the budgets.

The DOJ findings continued:

“The need to keep consumers’ resource allocations within budget may influence staff to administer the SIS in a way that reaches the pre-determined budgetary result.”

“Numerous persons stated that this lack of neutrality, and apparent tension between the need to assess the full spectrum of an individual’s support needs and state efforts to cut costs, has negatively. impacted the resources individually allocated to people with I/DD (intellectual or developmental disabilities “Further,” the DOJ said, “we received considerable feedback from parents, family members, advocates, direct support staff, and providers that the individuals administering the SIS lack the training, qualification, or experience working with individuals with I/DD necessary to make resource allocation decisions on behalf of individuals with I/DD.”

The DOJ also said that “we find that several formative practical and procedural barriers exist under Project Sustainability that contribute to individuals’ inability to access the resources, including funding allocations, that they need to purchase services like supported employment and integrated day planning.”

And the department found inflexibility in the requirement that workers be “face to face” with clients for their employers to receive reimbursement for services. Through the consent decree, the “face to face” provision has been eliminated in a pilot program to help adults with developmental disabilities seek regular jobs in the community.

Families and service providers routinely appealed adverse funding allocations, and many of them were successful, resulting in supplemental payments for a year. But the following year, they received notice that the supplemental payments would be withdrawn, and the appeal process began all over again.

Until Stenning left office in 2015, parents and service providers were denied copies of the actual SIS scores. Some parents have said BHDDH officials told them the questionnaires, developed by the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD), could not be released because they contained private propriety information.

That’s changed. Today developmental disability officials have acknowledged that the completed questionnaires are personal health care records that must be made available to patients or their guardians, according to federal law. BHDDH has never released the funding formula.

Parents also have complained publicly that social workers administering the interviews either argued with them and with providers about their responses or that they wrote down scores different from the ones offered by family members and providers.

AAIDD Defends SIS

Margaret Nygren, executive director of AAIDD, which created the SIS, said it is a “well-established, scientifically valid, replicable tool” designed to measure support needs, and those who administer it must complete a “very rigorous training program” that includes an “annual recheck to make sure they are not drifting what we are training them to do.”

“It is certainly possible someone could get through the training and not apply what they’ve learned,” she said. “It’s not the kind of thing we’d like to see happen,” Nygren said. But she suggested it would be the rare exception rather than the rule.

In December, 2015, Wayne Hannon, then Deputy Secretary of EOHHS for Administration, tried to get a handle on the amount of money that BHDDH spent on supplemental payments outside the regular funding authorization process. These supplemental payments are not reflected as a separate line item in the budget.

Hannon asked Burns & Associates to figure out how much money the state could save if all the supplemental payments were eliminated. In a nine-page memo, the consultants concluded that the state could save a total of $13 million if all the supplemental payments were curtailed, but they stopped short of recommending such a move, saying they did not have enough information to know if the supplements were in fact warranted or used.

In the analysis that led to the conclusion, Burns & Associates' figures suggested there was a great deal of variability in SIS scores, even though the needs of particular individuals usually can be expected to remain fairly constant over time. For example, about 40 percent of those who had been assessed twice over a three-year period, or 726 of 1,798 individuals, had a change in funding levels the second time around, according to the consultants. In a smaller sample of 599 individuals, Burns & Associates said about 54 percent of funding authorizations decreased and the remainder increased.

AAIDD’s Nygren, who saw the memo, said the changes have to do with the funding algorithm created by the state, not the SIS itself. A small change in SIS scores could result in a change in funding, depending on how the formula is constructed, she said. BHDDH has not responded to requests for the formula.

SIS And Funding Formula Updated

The extent to which re-assessments generated changes in funding authorizations, whether up or down, raised eyebrows when they came to the attention of state developmental disability officials in the summer of 2016.

At the time, the state had just promulgated a new policy declaring that the SIS would be administered solely on the basis of an individual’s need for support, in response to a federal court order that had been issued to enforce the consent decree.

Meanwhile, Jane Gallivan, an experienced administrator of developmental disability services, had just been hired as a consultant and interim director of developmental disabilities.

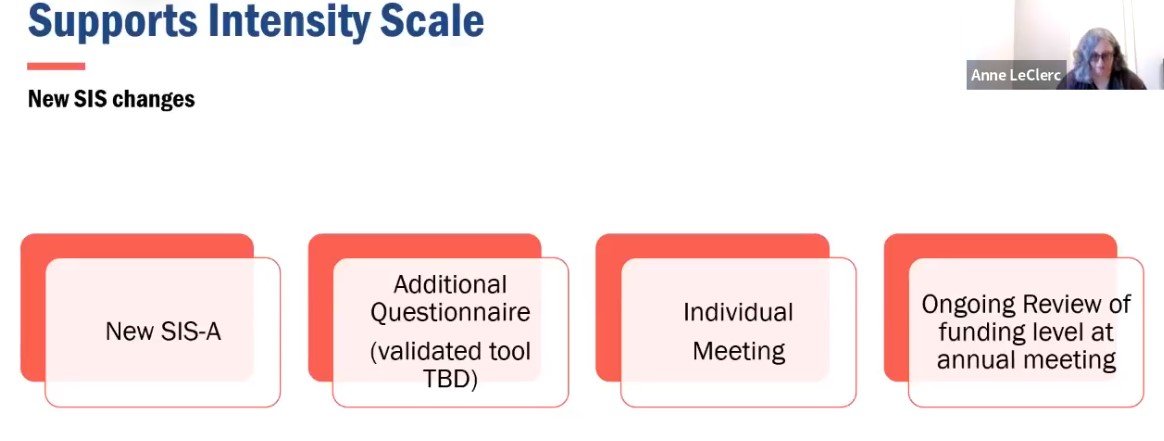

Gallivan later recommended the state switch to an updated version of the SIS, which she said she believed would be more accurate in capturing clients’ needs, particularly for those requiring behavioral and medical supports. Burns & Associates also was re-hired to re-tool the funding formula.

The conversion to the so-called SIS-A included the retraining of all the interviewers and was launched in November, 2016, in the hope that the number of appeals – and supplemental payments – will come down. Initial reports on the results of the SIS-A indicate that overall, they result in higher funding authorizations, according to developmental disability officials.

In the meantime, the current BHDDH budget allows for $18.5 million for supplemental payments, but in the first three quarters of the fiscal year the department went $3 million over that authorization, according to a recent House fiscal presentation. And Governor Raimondo seeks $22 million in supplemental payments in the fiscal year beginning July 1.

Taking in these numbers on overruns in the supplemental payments at a recent Senate Finance Committee hearing, Sen. Louis DiPalma told BHDDH officials to “look at the equation” that assigns funding authorizations to adults with developmental disabilities.

DiPalma and Rep. Teresa A. Tanzi, D-Narragansett and South Kingstown, have sponsored companion legislation that would make developmental disability caseload part of the semi-annual caseload estimating conference, used by both the executive and legislative branches of government to gauge expenses for Medicaid and public assistance.

DiPalma also has sponsored a separate bill that would require the SIS to be administered by an independent third party to avoid even the appearance of a conflict of interest.

AAIDD recommends that states take steps to ensure “conflict-free” administration of the SIS, a point noted by the DOJ in its 2014 findings.

Court Monitor Has A Say

The independent court monitor in the implementation of the consent decree would go a step further and uncouple the SIS from the funding mechanism altogether.

The monitor’s reports to the U.S. District Court say the SIS should be used for “person-centered planning,” a bedrock principle of the consent decree, which puts the focus on the needs and preferences of individuals, rather than trying to fit their services into a pre-determined menu of choices, as is now the case.

The monitor, Charles Moseley has said the SIS should be used as a guide for developing an individualized program of services, and then funding should be applied to deliver those services. Currently, the funding defines the scope of the services.

Moseley has put the state on a quarterly schedule of progress reports toward implementing “person-centered planning.”

The changes have as-yet undefined budget implications for the state in the future.

Tom Kane, CEO of AccessPoint RI, a provider, explained to a subcommittee of the House Finance Committee in a recent hearing that it will be inherently more expensive to provide services in the community than it has been historically to have one person working with ten clients in a room in a sheltered workshop or day program.

There is now only slightly more in the private developmental disability system than there was in 2010, he said. (The General Assembly has approved $218.3 million in reimbursements to private providers for the current budget cycle, or $10.2 million more than was spent in the fiscal year that ended June 30, 2010, according to state budget figures.)

“There are more people in the system” and “the requirements of the consent decree are far more extensive than the kind of supports we were providing,” Kane said.

He said he’s “definitely in favor” of Governor Gina Raimondo’s budget proposal, which would add $10 million to the system over the next 15 months, but he believes the available funding is only half of what is needed to stabilize private provider agencies and ensuring their clients get the “services they deserve and require.”